संत्रिका सुवर्ण महोत्सव

५ जून २०२५

लेख क्र. २

या भागात श्री.अर्जुनवाडकरांनी संस्कृतचे देशासाठी काय महत्त्व आहे, त्या महत्त्वाला अनुसरून संत्रिका-विभागाचे काम काय असेल, याबद्दलचे त्यांचे प्रदीर्घ चिंतन मांडले आहे. हे लिहिताना सध्याच्या शिक्षण व्यवस्थेबद्दल तीव्र नाराजीही व्यक्त केली आहे. संस्कृतच्या अभ्यासकांनी संस्कृत सोबत पाली,प्राकृतचे ज्ञान करून घ्यायला पाहिजे असे लिहिताना;

१.संस्कृतमधील संशोधन अधिक समाजोपयोगी व विस्तृत पायावर आधारित होणे.

२.अभ्यासाच्या जुन्या परंपरा व नवीन पद्धती यांचा मेळ घालता येणे.

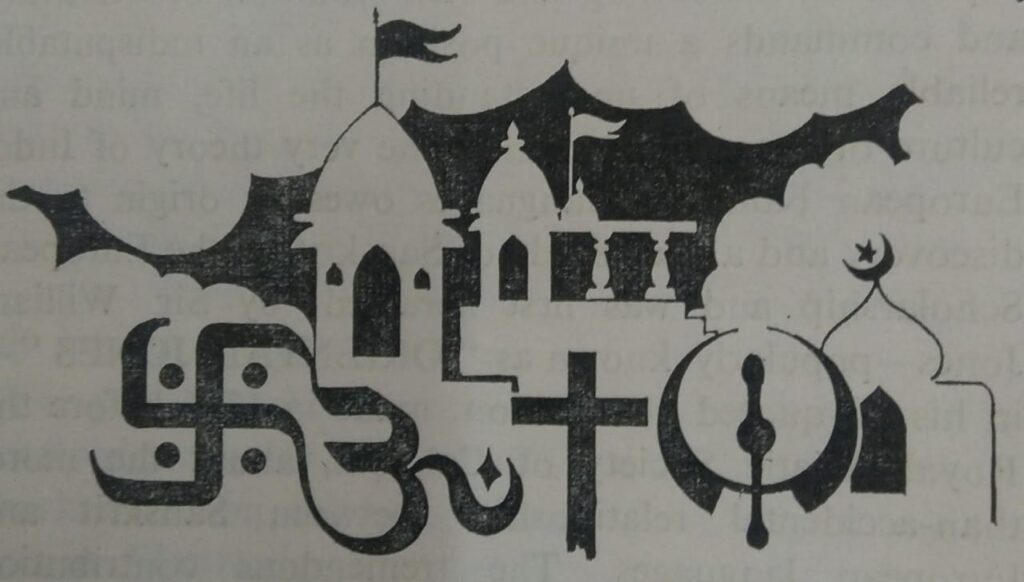

३.संशोधनास व्यापक पायावर आधारित बनवून समाजाच्या गरजा आणि आकांक्षा पूर्ण करण्याची प्रेरणा निर्माण होणे व त्यासाठी कठोर परिश्रम करण्याची गरज त्यांनी व्यक्त केली आहे, ज्यामुळे विविध विचारसरणी, पंथ, परंपरा, धार्मिकविचार, विविध राष्ट्रांना समजून घेता येईल…

National Value of Sanskrit

Equally important is the role Sanskrit has played on the national stage. It has nurtured the Indian brain and mind, speech, and culture for more than four millennia, not discriminating between the orthodox and the heterodox, the religious and the secular, or the spiritual and the material. ‘The Indian people and the Indian civilization were born, so to say, in the lap of Sanskrit.’ (Report of the Govt.of India Sanskrit Commission.) Even while it flourished as a pan-India medium of the learned, Sanskrit let the Prakrits freely draw upon it for content as well as expression, and for the modern Indian languages struggling to keep pace with the fast-moving world of science and technology, Sanskrit is a veritable source of strength, as is blood in any organic system. And this has not been only a one-way traffic; since, through long centuries of its activity as an all-India language, Sanskrit, too, absorbed quite a few elements from Sanskritic and non-Sanskritic linguistic stocks. Sanskrit, thus, is a true symbol of Indian unity. If the Indian people are one nation and not half a dozen or more nations, it is certainly due to Sanskrit. This debt to Sanskrit is acknowledged by Jawaharlal Nehru in the most expressive and unequivocal terms: ‘If I was asked what is the greatest treasure that India possesses and what is her finest heritage, I would answer unhesitatingly—it is the Sanskrit language and literature and all that it contains. This is a magnificent inheritance, and so long as this endures and influences the life of our people, the basic genius of India will continue. (Ibid., p. 72) India is to the world ‘the land of Sanskrit’ and one of the most ancient cradles of civilization. India without Sanskrit would, like a man without a face, forfeit identity, status, and goodwill. It is, therefore, both a duty and a self-interest for us Indians to preserve and nourish Sanskrit.

Preservation of Sanskrit on Research Level

How well we can do it is the next question, which can be answered on two levels: the research level and the popular level. Before the advent of the university system in the wake of British rule in India, the indigenous system of Pathashalas took care of Sanskrit education at the primary, secondary, and higher levels. It had its own strong points, and products of this system surpassed those of the university system in depth. They, however, lacked the comparative and historical outlook, a gift of the newly introduced university education, and the overall perspective that such an outlook lends to the student. Under the tremendous pressure of the changed conditions, needs of the time, and practical considerations, the old system slowly gave way to the new one. It no longer attracted the best brains, which fact naturally resulted in poor results. The university system, too, planned to work on the lines conceived by and suited to the needs and conceptions of its foreign sculptors but failed to produce results comparable in depth to those of the old system, which the new one supplanted. To use the expressions of a veteran Maharashtrian educationist, the old system produced the ‘misfit,’ while the new one produced the ‘counterfeit.’ Neither system produced just the ‘fit.’

The Santrika Way

Given the legacy of the two systems vying with each other in failure, SANTRIKA had to work out its own system, which would combine the strong points of both and develop additional sources of strength, furnish a purpose that would attract the best brains to Sanskrit and allied studies, and provide a utility that would counterbalance the support for such studies expected of the society. This new system would be such as to provide for

i) Rigorous training under the masters of the old system as well as those of the new one;

ii) Equipment that would lift up the student above the conventional research arena, place in his hands the basic tools of research, and make his studies truly critical, comparative, and historical; and

iii) A motivation to make the research fulfil the needs and aspirations of the society by making it broad-based, leading to understanding between different schools, sects, traditions, religious provinces, or nations.

The Ailment and the Cure

Research fulfilling these conditions is bound to be interdisciplinary, requiring guidance from experts in different subjects and efforts from the student to acquire sufficient grounding in essential and supplementary equipment. The present Sanskritist in India knows little beyond Sanskrit, not even Pali and Prakrit, which are two more facets of Sanskrit itself, while his counterpart in Europe and North America is required to know, beyond Sanskrit, ancient and modern world languages and subjects related to Sanskrit or his special field of research. No wonder, then, that research degrees in foreign countries are rated higher than those in our country. Indian Sanskritists rarely turn to, or are encouraged to turn to, cross-cultural subjects requiring equipment to deal with firsthand Arabic, Tibetan, Chinese, Ceylonese, or similar sources; if at all he chooses subjects from these areas, he has to rely on second hand sources like English translations, good or bad, of the firsthand material. The reason is our research worker is never taught to think this way.

SANTRIKA would be justified in adding one more to the already existing institutes in this field if it does not duplicate the existing research pattern and produces results along the lines envisaged above. Efforts are being made to work out programs for SANTRIKA geared to produce results as outlined earlier—e.g., study circles for advanced works in Mimamsa and Vedanta, for Avesta, dramaturgy, and classes for teaching Tibetan and Bengali (Chinese, Arabic, and Tamil will soon follow suit). A beginning is made for the study of astronomical works in Sanskrit, and plans are under way to study Sanskrit works on other positive sciences and subjects like engineering.

क्रमशः