In a vast and diverse country like India, the fair distribution of resources among the states is challenging due to differing regional needs and economic conditions. The federal governance system, with shared powers and responsibilities between the Centre and states, often sparks conflicts over resource allocation. Recently, debates on the North-South divide in resource sharing have brought this issue into focus. Southern states believe they are not receiving their rightful share of the tax transfers they deserve, despite making higher economic contributions and experiencing better social progress.

To understand the evolution of India’s fiscal structure, it is essential to examine historical patterns of resource sharing across different empires and governance systems. Under rulers like Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire implemented a centralised system with clear administrative divisions to streamline tax collection. In contrast, the Gupta Empire favoured a decentralised approach, where local rulers and landowners collected taxes and retained a portion for local administration. Later, during Akbar’s reign, the Mughal Empire refined Sher Shah Suri’s land revenue system through the Todar Mal bandobast. The empire was divided into provinces (subas), each governed by an official responsible for local finances and revenue collection, which was then directed to the central treasury. The Marathas further innovated with the Chauth and Sardeshmukhi (additional levy) tax systems, allowing provinces to retain a share of revenue while remitting a fixed portion to the central authority. Moving into the 20th century, the Government of India Acts of 1919 and 1935 established the framework for modern fiscal federalism, dividing revenue sources between the centre and the state.

After independence, the Indian Constitution established a flexible financial system to address regional inequalities and adapt to changing needs. While the central government collects most of the tax revenue, states are tasked with providing public services due to their closer proximity to local needs. However, uneven development across states often leaves some unable to generate sufficient resources, resulting in expenditures exceeding their revenues. To address these imbalances and ensure the fair distribution of central funds among states while promoting balance, the Finance Commission (FC) plays an integral role, drawing inspiration from Australia’s Commonwealth Grants Commission (1933). It is important to note that the FC does not recommend funds for Union Territories; the central government provides them through grants and schemes.

Structure of the FC

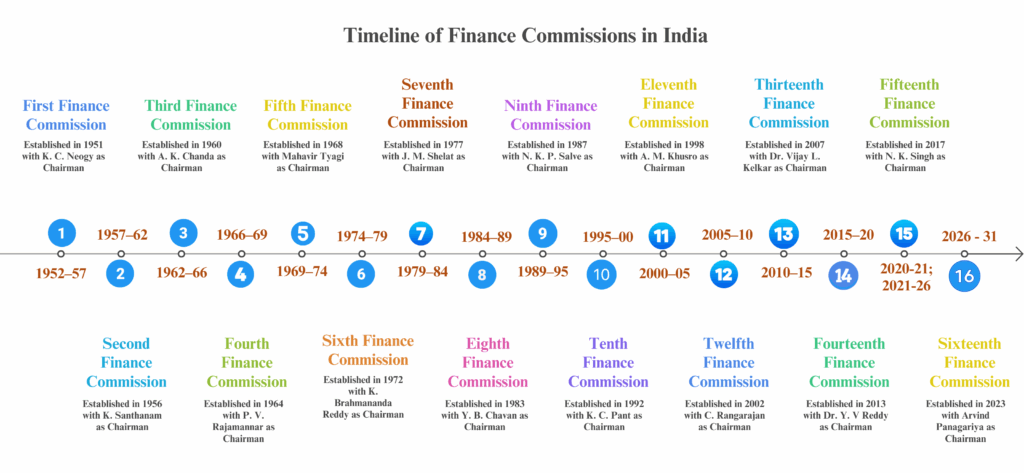

The FC of India was established in 1951 under Article 280 of the Constitution, which mandates the President to constitute a FC within two years of the Constitution’s adoption and subsequently every five years, or earlier if required. To ensure transparency, Article 281 requires the President to present the Commission’s recommendations to Parliament, though these recommendations are advisory and not binding, leaving their implementation at the discretion of the Union Government. The Union government has always accepted the recommendations of the FCs, except for the 3rd FC’s recommendations relating to Plan grants.

The FC Act of 1951 outlines the qualifications for its members. The Commission consists of a Chairman, who must have experience in public affairs, and four other members chosen based on specific criteria.

-

- A judge of the High Court or someone qualified to be appointed as one.

-

- An expert in government finance and accounts.

-

- An individual with extensive experience in financial matters and administration.

-

- An economist with recognised expertise.

Similar to the FC at the national level, the State Finance Commission (SFC) aims to maintain a fair and balanced financial relationship between state governments and local bodies. The Governor sets it up based on the recommendations of the state government. However, only fifteen states have established their 5th or 6th SFC, while several others have not progressed beyond the 2nd or 3rd SFC. This delay is largely due to state governments not constituting SFCs on time or prioritising their role. Key challenges include inadequate office space, a lack of technical staff, insufficient infrastructure, the unavailability of local government financial data, and limited expertise. Additionally, most SFC members and chairpersons are bureaucrats and politicians, which can affect the quality and independence of recommendations.

Note: The restrictions imposed by the Model Code of Conduct delayed the commission’s work, causing it to complete its state visits later than expected. As a result, its detailed assessment of different states’ requirements was affected. To address this, the Union Cabinet extended the term of the 15th FC by one year. Consequently, the Commission submitted two reports—one for the fiscal year 2020-21 and another covering the financial years 2021-22 to 2025-26.

Functions of the FC

The terms of reference defined by each commission govern the function it is tasked with carrying out. These Terms of Reference (ToR), derived from Article 280(3) of the Indian Constitution, require the Finance Commission to provide recommendations to the government on key financial matters. These include: i) Deciding how much of the Centre’s tax revenue should go to the States (vertical sharing). ii) Determining each State’s share in the total pool of Central taxes (horizontal distribution). iii) Recommending Grants-in-Aid to states that require financial support for their revenues. iv) Suggest ways to strengthen the Consolidated Fund of States to help Panchayats and Municipalities with additional resources. v) Under Article 280(2)(c), the President can assign any other financial matters to the Commission if necessary for better fiscal management. These include improving government efficiency and transparency in administration, as well as creating financial plans to support states during emergencies, such as natural disasters.

In this article, we will focus on two key functions: 1. Tax devolution and 2. Grants-in-aid of the revenues of the States.

Tax Devolution

A key responsibility of the FC, as outlined in Article 280(3)(a) of the Constitution, is tax devolution. This refers to the FC’s role in recommending how tax revenues should be distributed between the central government and state governments. It is the most important function of the FC, as tax devolution is the primary means by which the Centre transfers resources to the states. Tax devolution is carried out in two steps: 1) Vertical devolution and 2) Horizontal devolution.

The Finance Commission determines the proportion of the Centre’s net tax revenue to be shared with the States. This share, known as the divisible pool, includes taxes such as corporation tax, personal income tax, Customs duty, Central Goods and Services Tax (CGST), and the Centre’s share of Integrated Goods and Services Tax (IGST). However, cesses and surcharges—which made up about 28% of the Centre’s gross tax revenue in 2021–22—are excluded from the divisible pool and remain with the Centre. This allocation of tax revenue between the Centre and the States is known as vertical devolution. Once the total divisible pool (tax devolution + grants) is determined, the FC decides each state’s share through a process known as horizontal devolution. To ensure fair tax devolution among all 28 states, the FC allocates shares using specific parameters, broadly grouped into need-based, equity-based, and performance-based criteria.

The first FC recommended sharing 55% of income tax revenues with states and 40% of Union excise duties. As states’ expenditure needs grew, states’ share in the net proceeds of union taxes grew over time. The 10th FC later proposed that states benefit from the buoyancy of all Central taxes and enjoy predictable resource flows. Acting on this, the 80th Constitutional Amendment (2000) included all Central taxes on goods and services—except cesses and surcharges—in the divisible pool.

Table 2: States’ Share in Central Taxes Across Finance Commissions

| Finance Commission (Period) | State’s Share in Net Proceeds of | ||

| Income Tax (%) | Union Excise Duties (%) | All Shareable Union Taxes (%) | |

| FC-1 (1952-57) | 55 | 40 | |

| FC-2(1957-62) | 60 | 25 | |

| FC-3(1962-66) | 66.66 | 20 | |

| FC-4(1966-69) | 75 | 20 | |

| FC-5(1969-74) | 75 | 20 | |

| FC-6(1974-79) | 80 | 20 | |

| FC-7(1979-84) | 85 | 40 | |

| FC-8(1984-89) | 85 | 45 | |

| FC-9-I(1989-90) | 85 | 40 | |

| FC-9-II(1990-95) | 85 | 45 | |

| FC-10(1995-00) | 77.5 | 47.5 | |

| FC-11(2000-05) | 29.5 | ||

| FC-12(2005-10) | 30.5 | ||

| FC-13(2010-15) | 32 | ||

| FC-14(2015-20) | 42 | ||

| FC-15-I(2020-21) | 41 | ||

| FC-15-II(2021-26) | 41 | ||

Source: Finance Commission Reports

For the 2021–26 period, the 15th FC recommended that States receive 41% of the divisible pool, amounting to ₹42.2 lakh crore. In addition to this tax devolution, the Commission also recommended total grants of ₹10.33 lakh crore. Together, the aggregate transfers to States are estimated to account for approximately 50.9% of the divisible pool during this period.

While considering total resource transfers to states, tax devolution has consistently formed the major component. Since the 1st FC, on average, over 84% of the transfers recommended by the 1st to the 12th FCs have been through tax devolution.

The share of tax devolution has fluctuated significantly over the years. For instance, in the 6th FC (1974-79), only 73.9% of total transfers were allocated through tax devolution. This figure saw a substantial increase in the 7th FC (1979-84), where the share rose to 92.2%. However, in the following years, the tax devolution percentage declined. The 11th FC recommended 86.5% of transfers through tax devolution, and more recently, the 15th FC suggested a share of 80.3%.

Grants-in-Aid

Based on the FC’s recommendations, states receive grants-in-aid of the revenues of the States from the Centre to support development projects or address revenue shortfalls. Under Article 275 of the Constitution, the FC is responsible for recommending both the principles and the amount of grants for states in need of financial assistance. These transfers help bridge financial gaps and promote equitable development by targeting specific states or sectors in need of support or reform.

These grants are allocated from the Consolidated Fund of India, the government’s primary account that holds all revenues, including taxes and loans, for expenses such as state grants. Grants are of two types: tied and untied. Tied grants come with specific conditions, restricting their use to designated areas or purposes. In contrast, untied grants provide states with the flexibility to allocate funds according to their own needs and priorities without restrictions. For example, out of the total grants earmarked for Panchayati Raj institutions, 60% are tied and allocated for national priorities such as drinking water supply, rainwater harvesting, and sanitation. In contrast, 40% are untied, allowing Panchayati Raj institutions to use them at their discretion for improving basic services.

It is important to note that grants-in-aid of the revenues of the States are distinct from the divisible pool, as they are not part of it.

Grants-in-aid of the revenues have fluctuated significantly over time. Under the Sixth FC (1974-79), they accounted for 26.1% of total transfers, but this dropped sharply to 7.7% under the 7th FC (1979-84). The 12th FC (2005-10) experienced a rebound, with grants accounting for 18.9% of total transfers. For the 15th FC (2021–26), grants are 19.6% of total transfers. These shifts are influenced by economic conditions, the central government’s financial health, tax revenue trends, and political dynamics. Note that the operational period of the 6th FC (1974-79) coincided with pre-emergency and emergency years, while the 7th FC was established during the tenure of the first non-Congress government in the aftermath of the emergency.

Table 3: Grants in aid vs. tax devolution (% of total Finance Commission Transfers)

Source: Finance Commission Reports

Grants from the Centre to states are of two types: statutory and discretionary.

-

- Statutory Grants: Article 275 allows Parliament to provide financial grants to states that need assistance. The amount of these grants can vary each year and is taken from the Consolidated Fund of India, based on the recommendations of the FC. The reason these are called Statutory Grants is that they are sanctioned by a specific parliamentary law.

- Discretionary Grants: Article 282 allows both the Centre and states to provide discretionary grants for public purposes beyond their legislative competence. These grants, allocated based on need, priority, or emerging situations, typically lack a fixed formula and are often substantial. They enable states to meet plan targets while giving the Union Government leverage to align state policies with national priorities. Discretionary transfers, often linked to centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) or special projects, grant the Centre significant control over fund distribution. Previously, the Planning Commission played a key role in recommending such grants, particularly in the early years after independence, when they often exceeded statutory allocations.

The following grants are generally provided to states from the centre’s resources:

-

- Revenue Deficit Grants: To eliminate revenue deficits of the state.

-

- Grants to Local Bodies: For local development and health initiatives, often with performance-linked conditions.

-

- Disaster Risk Management Grants: For disaster preparedness and response.

-

- Sector-Specific Grants: Focused on health, education, agriculture, roads, judiciary, and more.

-

- State-Specific Grants: Addressing the unique needs of each state, such as infrastructure or social services.

Table 4: Grants for 2021-26 (15th FC) (Rs crore)

| Grants | Revenue deficit grants | Local governments grants | Disaster management grants | Sector-specific grants | State-specific grants | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | 294514 | 436361 | 122601 | 129987 | 49599 | 1033062 |

*Note: The table is provided as an example to give readers an overview of how the grants are distributed.

Interestingly, the Constitution also provided for a special type of grants-in-aid of the state’s revenues under Article 273 for a temporary period after India’s independence. For a decade (until 1960), states that grew jute—such as West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, and Assam—received grants-in-aid from the Union. These grants were linked to the export duty on jute products, offering financial support based on the export of jute.

In conclusion, the FC undeniably plays a pivotal role in shaping India’s fiscal federalism through its structured approach to resource distribution. This article provided an overview of its evolution, structure, functions, and basic concepts. In the next article, we will examine in detail the formula designed by the 15th Finance Commission for allocating taxes among states, which has sparked controversy and drawn significant attention in recent years.

Ishant Deshmukh, Research Assistant, JP-SSSC

If you want to communicate with us, kindly write to [email protected]