This year, the government has rolled out a broad wave of economic reforms – from changes in personal income taxation to stepped-up trade negotiations with global partners. Many of these measures seek to introduce structural changes while addressing growing global trade uncertainty, especially the impact of rising U.S. tariffs on key export markets.

One area that has once again come into policy focus is indirect taxation. Eight years after the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), India’s most ambitious indirect tax reform continues to evolve, with recent GST rate rationalisation marking an important step in this ongoing journey.

Through this article, we aim to develop a clear understanding of India’s indirect tax system, the GST framework, recent policy updates, and how these changes should be viewed in the broader economic context. The article also explores the challenges that persist within the current GST structure and considers possible directions for reform going forward.

Issues in Indirect Taxation before the Introduction of GST

An indirect tax in India is a tax levied on goods and services by the government, rather than directly on income or profits. They are called indirect taxes because the tax is collected by an intermediary, such as a manufacturer or retailer, who then passes the burden onto the consumer through the price of the product. This is different from direct taxes, such as personal income tax or corporate tax, which are borne directly by the individuals or entities on whom they are imposed.

Indirect taxes constitute a significant source of revenue for the Indian government, but they have shown a decreasing trend over the years, accounting for approximately 42% of the country’s gross tax revenue in FY 2023–24.

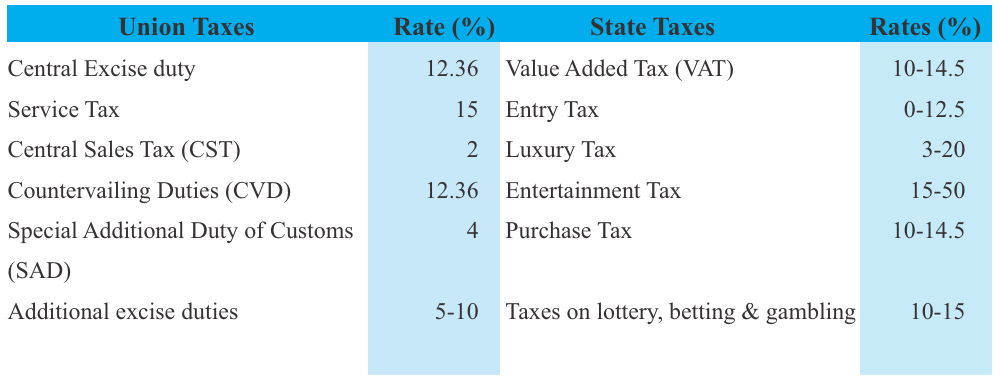

Before the introduction of the GST, there existed multiple indirect taxes at both the central and state levels. Central taxes included Central Excise Duty, Additional Excise Duties, Additional Duties of Customs, and Service Tax, while state-level taxes comprised State Value Added Tax, Central Sales Tax, Luxury Tax, Entertainment and Amusement Tax, and various surcharges and cesses.

These multiple taxes were levied at different stages of production and distribution, often being charged one on top of another. One tax was added to the price first, and then the next tax was calculated on that higher price, which resulted in double taxation and a cascading or “tax on tax” effect. This cascading effect increased the cost of goods and services and made the pre-GST indirect tax regime inefficient and complex.

This can be explained by the following illustration –

Stage | Seller → Buyer | Value Added (₹) | Base Value (₹) | Tax @10% (₹) | Price Paid (₹) | Tax to Govt. (₹) |

1 | Cotton Supplier → Yarn Manufacturer | 100 | 100 | 10 | 110 | 10 |

2 | Yarn Manufacturer → Fabric Producer | 100 | 110 + 100 = 210 | 21 | 231 | 21 |

3 | Fabric Producer → Garment Manufacturer | 100 | 231 + 100 = 331 | 33.1 | 364.1 | 33.1 |

4 | Garment Manufacturer → Garment Retailer | 100 | 364.1 + 100 = 464.1 | 46.41 | 510.51 | 46.41 |

5 | Garment Retailer → Consumer | 100 | 510.51 + 100 = 610.51 | 61.05 | 671.56 | 61.05 |

Total Tax to the Govt. – 171.56≈172 Note: The value addition at every step in the supply chain is ₹100, and a 10% tax is applied throughout the chain for the reader’s convenience. | ||||||

In this example of the textile value chain, from the cotton supplier to the final garment retailer, each stage adds a value of ₹100 and is charged a 10% tax on the total selling price, which already includes the tax paid at the previous stage. As a result, the price of the product balloons, and the total tax collected by the government amounts to a whopping ₹172. While this system generates higher revenue for the government, it comes at the expense of businesses and consumers, as prices rise at every stage, increasing production costs and reducing competitiveness.

In 2005, the introduction of Value Added Tax (VAT) was intended to reduce the cascading effect of taxes by providing a mechanism called Input Tax Credit (ITC), whereby the tax paid on purchases (input tax) could be claimed against the tax payable on sales (output tax). It eliminates the cascading effect by ensuring that tax is levied only on value addition, thereby preventing duplication across the production chain.

However, VAT had several issues: input claims were allowed only on goods and not on services, VAT laws and rates differed across states, and VAT paid on raw materials could be used to pay the Central Sales Tax (CST) on inter-state sales of finished goods, but CST paid on purchases could not be claimed as credit.

Understanding the Goods and Services Tax

To address inefficiencies in the existing taxation system and to simplify taxation across the supply chain, GST was introduced in July 2017. The concept was first proposed by Dr. Vijay Kelkar, Dr. Ajay Shah, and Mr. Arbind Modi who recommended a comprehensive GST framework for India in July 2004. It took several years for the idea to take shape and be implemented.

GST is an indirect, destination-based tax that replaced several central and state levies in India. It is a comprehensive, multi-stage tax applied to the supply of goods and services and levied at each stage of value addition. It streamlined the taxation process, reduced the multiplicity of levies, and eliminated the cascading effect of “tax on tax,” making the system more transparent and business-friendly. GST has further simplified procedures through a common IT platform (GSTN), unified return filing, digital tracking of invoices, and reduced paperwork.

Taxes Subsumed in GST and Their Rates.

It was designed to realise the vision of “One Nation, One Tax” by creating a uniform tax regime across states, reducing price distortions, promoting formalisation, and improving tax revenue through greater efficiency.

A more comprehensive form of Input Tax Credit was introduced under GST, which now covers both goods and services, preventing taxpayers from paying tax multiple times on the same product or service. It eliminates issues arising from VAT and smooths the supply chain.

|

Stage |

Seller → Buyer |

Value Added (₹) |

Base Value (₹) |

Tax @10% (₹) |

Price Paid (₹) |

Input Tax Credit (ITC) (₹) |

Tax to Govt. (After ITC) (₹) |

|

1 |

Cotton Supplier → Yarn Manufacturer |

100 |

100 |

10 |

110 |

0 |

10 |

|

2 |

Yarn Manufacturer → Fabric Producer |

100 |

200 |

20 |

220 |

10 |

20-10 = 10 |

|

3 |

Fabric Producer → Garment Manufacturer |

100 |

300 |

30 |

330 |

20 |

30-20 = 10 |

|

4 |

Garment Manufacturer → Garment Retailer |

100 |

400 |

40 |

440 |

30 |

40-30 =10 |

|

5 |

Garment Retailer → Consumer |

100 |

500 |

50 |

550 |

40 |

50-40 = 10 |

|

Total Tax to the Govt. – 50 |

|||||||

Coming back to our example of the textile value chain, taxpayers now pay tax on their inputs (raw materials and services) and accumulate ITC at the time of purchase. This accumulated credit can then be used to offset the tax payable on their sales, ensuring that tax is paid only on the value added at each stage of production. Now, the consumer pays ₹550 for the garment, lower than what they paid in the earlier example, and the government ultimately collects only ₹50 in tax, instead of ₹172. This is because every seller adjusts the tax already paid on inputs through ITC and remits only the balance on their own value addition, thus effectively eliminating the cascading effect.

By creating a seamless value-added tax chain, GST eliminates tax cascading and improves the flow of input tax credit. GST makes taxation neutral to the nature of the value chain. As a value-added tax, it also has a self-policing mechanism: buyers can claim credit only if sellers report transactions and pay tax, which encourages compliance and limits tax evasion. Most importantly, GST reduces the influence of taxes on business decisions. Earlier, companies often chose how to transport goods or where to locate warehouses and factories based on tax advantages. With GST applying uniformly across states, such decisions are now driven more by efficiency and business needs rather than tax considerations.

Challenges in the Initial GST Framework

Despite its ambitious design, the GST Act soon replaced one set of complications with another. India’s initial GST framework was among the most complex in the world, with five major tax slabs – 0%, 5%, 12%, 18%, and 28%, along with cesses. This structure created confusion, frequent disputes, and tax evasion. Even minor differences in packaging or branding could change the tax rate. For example, salted popcorn sold loose was taxed at 5%, packaged at 12%, and caramel popcorn at 18%. These inconsistencies led to compliance challenges, particularly for small traders.

Multiple slabs also forced firms to constantly update their billing systems and maintain detailed classifications, diverting resources from productivity and innovation. Moreover, similar goods were taxed differently, leading to disputed price gaps and violating the principle of tax fairness. Globally, most countries follow simpler GST or VAT models, such as Australia (10%), Indonesia (11%), New Zealand (15%), Finland (25.5%) and Hungary (27%). In contrast, India’s multi-rate system has made compliance challenging and reduced tax efficiency.

The late former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley explained in 2017 that a single-rate GST is not feasible in India, as it can only work in a country where purchasing power is uniform. He further noted that as GST revenue grows, policymakers might have the opportunity to merge the 12% and 18% slabs into a single rate, effectively simplifying the GST structure to two rates.

Rate Rationalisation and Its Impact on Consumption

Recognising these challenges of multiple slabs, the GST Council introduced a major rate rationalisation in September 2025. India has now moved from 5 main slabs to a 3-rate structure – 5%, 18%, and 40%. Under the revised structure:

● Food and dairy products: Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) milk, pre-packaged and labelled chena or paneer, pizza bread, and Indian breads such as khakhra, roti, and paratha are exempted from GST.

● School essentials: Notebooks, pencils, maps, and crayons are now exempt from GST.

● Food and household items: GST on butter, ghee, namkeens, utensils, and baby care products dropped from 12% to 5%.

● Medical items: Items such as thermometers, oxygen, diagnostic kits, and spectacles now attract 5% GST, easing medical costs for low-income households.

● Agricultural support: GST on fertilisers, irrigation systems, and farm machinery has been reduced from 12% to 5%.

● Consumer essentials: GST on shampoo, toothpaste, soap, hair oil, and shaving cream fell from 18% to 5%.

● Services: Individual health and life insurance premiums reduced from 18% to zero, Hotel rooms priced up to ₹7,500 will now attract GST at 5%, down from 18%.

● Urban household goods: GST on refrigerators, dishwashing machines, and TVs fell from 28% to 18%, helping the urban middle class.

● Luxury and sin goods: A special high tax slab of 40% has been created for luxury and sin goods, which includes all types of aerated water, carbonated beverages, caffeinated drinks, non-alcoholic beverages, and motorcycles with an engine capacity above 350cc.

With 99% of goods in the 12% slab moved to 5%, and 90% of items in the 28% slab reduced to 18%, this restructuring will not only simplify compliance but also boost the purchasing power of India’s middle class. Households with a high marginal propensity to consume, particularly middle- and lower-income groups, will benefit the most, as they spend a large share of their income on everyday essentials. Lower taxes on items such as toiletries, food products, dairy, utensils, and home appliances will increase disposable incomes, driving stronger consumption and demand across FMCG, consumer durables, and agriculture-linked sectors.

The GST rate cuts followed the personal income tax relief introduced earlier this year, which raised the annual exemption limit from ₹7 lakh to ₹12 lakh. Due to the GST cuts, the government has forecasted a revenue forgone of around ₹48,000 crore. According to an SBI report published in August 2025, for FY26, the revenue forgone could be around ₹45,000 crore, close to the government’s estimate, but the cuts are expected to boost consumption by approximately ₹1.98 lakh crore. When combined with the personal income tax cuts, the total impact of both measures amounts to an additional ₹5.31 lakh crore in consumption expenditure, equivalent to about 1.6% of GDP.

Experts favoured GST cuts over other measures because, while income tax is paid by only about 1–2% of the population, GST reductions benefit a much broader base of consumers. Since GST is paid by everyone, regardless of income, lowering its rates provides immediate relief to households across all income levels, especially those in the middle- and lower-income groups.

The fiscal multiplier effect illustrates this clearly. GST has a fiscal multiplier of 1.08x, income tax 1.01x, and corporate tax 1.02x. This means that for every ₹1 of GST revenue forgone, the economy expands by ₹1.08. Consumers directly feel the impact because goods become cheaper, leading to higher demand, increased production, more employment and income, and further spending. This multiplier is larger because it affects everyone, unlike income and corporate tax measures, which target specific segments of the population. Simply put, GST cuts generate the strongest growth impact among all tax measures.

Domestic Demand as India’s Shield Against Global Shocks

This consumption-led boost is especially crucial for those employed in labour-intensive and small-scale sectors, as India has recently faced new external challenges, notably the 50% tariff imposed by the United States on key Indian exports such as textiles and apparel, leather and footwear, marine products, chemicals, and automobile components. Exports have never been India’s forte, and the country has long aspired to, but not quite managed to, match the export success of other Asian powerhouses. However, for a nation that has never been heavily export-dependent, fluctuations in the export sector can be balanced by growth in other areas of the economy.

The GST rate cuts are expected to absorb part of this external shock. With domestic consumption now forming around 60% of India’s GDP, the country is better positioned to rely on internal demand as a buffer. Consumption has been India’s core strength, the backbone of its economic resilience and growth. By stimulating internal demand through lower GST rates, India is effectively turning its domestic consumer base into a shield against global trade headwinds, a strategy noted even by The Economist, which described India’s consumers as “Modi’s secret weapon.” This reflects an effort to make the Indian consumer the shock absorber amid global tariff disruptions.

The impact of these rate cuts became evident in October. Gross GST collections for October 2025 stood at ₹1,95,936 crore, reflecting a year-on-year monthly growth of 4.6% compared to October 2024.

Diwali this year recorded a historic milestone, with total sales surpassing ₹6 lakh crore, the highest Diwali business in India’s trading history. This data comes from the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT), a national organisation representing over 9 crore traders and small businesses. CAIT conducted an extensive pan-India survey across 60 major distribution centres, covering Tier-1, Tier-2, and Tier-3 cities, with respondents including trade associations, individual traders, and consumers, from September 29 to October 20, 2025.

Major highlights of the survey:

• Goods sales: ₹5.40 lakh crore

• Services: ₹65,000 crore

• Growth over 2024 (₹4.25 lakh crore): 25% increase

The survey indicates that this surge was driven by improved consumer confidence, stable prices, and the Vocal for Local campaign, with 87% of consumers choosing Indian-made goods, thereby reducing demand for Chinese imports. Rural and semi-urban regions accounted for 28% of total sales, indicating that the recovery in consumption has expanded beyond metropolitan areas.

The category-wise sales distribution, based on the CAIT survey, can be understood through this pie chart.

However, this spike in October consumption should be interpreted with some caution. Part of the surge may reflect pent-up demand, particularly for discretionary items such as automobiles and large consumer durables, where GST rate rationalisation was anticipated in late September. This interpretation is reinforced by subsequent data: India’s gross GST collections in November 2025 declined to ₹1.70 lakh crore, a 12-month low, registering a modest year-on-year growth of just 0.7%, the weakest since the COVID-19 pandemic, and a sharp 13.4% fall from October’s ₹1.96 lakh crore. The moderation in November collections suggests that a portion of the October surge may have been driven by the timing of purchases rather than a sustained acceleration in underlying demand.

Towards a More Efficient GST

With the recent changes, the GST structure has undergone much-needed and welcome reforms. However, the system must still address several existing anomalies that continue to hinder the goal of achieving a clean and seamless tax framework.

ITC Blockages and the Burden of Inverted Duty Structure:

The ITC mechanism, the heart of GST and one of its most progressive features, continues to face operational challenges. Businesses frequently experience credit blockages, where taxes already paid on inputs cannot be claimed back promptly. These blockages or delays force taxpayers to pay GST on inputs that have effectively been taxed multiple times, creating a cascading effect that raises production costs and, eventually, consumer prices.

A significant cause of such distortions is the Inverted Duty Structure (IDS), a situation where taxes on inputs are higher than those on finished goods. This mismatch results in the accumulation of unutilised ITC. For instance, inputs like ammonia and sulphuric acid attract 18% GST, while fertilisers, their final output, are taxed at only 5%. To make things more complex, the output tax is levied on the subsidised value of the product, which is lower than its actual production cost, further reducing the output tax liability and widening the gap. The resulting credit accumulation strains working capital, particularly for small manufacturers.

Delays or denials in refunding these credits worsen the problem. In many states, refund approvals remain inconsistent, and several disputes remain unresolved due to a lack of clear administrative guidance. When businesses cannot get their refunds quickly, the blocked funds result in an additional cost, often passed on to consumers through higher prices.

Refund delays are also linked to the government’s tighter scrutiny in response to ITC-related frauds, which account for ₹1.78 lakh crore, nearly 25% of the ₹7 lakh crore in GST evasion detected between FY20 and FY25, according to Finance Ministry estimates.

Export Issues

Another area requiring attention is exports. Faster GST refunds could significantly enhance the global competitiveness of Indian exporters, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which contribute nearly half of India’s total export value. Yet, these firms often face delays in refunds and compliance issues. Operating on thin margins, even short-term refund delays can severely restrict their liquidity and undermine their competitiveness in international markets. Especially now, after being hit by 50% tariffs from the US, these reforms are more necessary than ever.

The GST Council’s recent decision to release 90% of refund claims upfront is therefore a positive step. Under this system, businesses affected by IDS will receive most of their refunds provisionally after automated risk checks. However, its effective implementation and timely follow-up will be crucial to ensure that the benefits reach taxpayers without procedural delays.

Petroleum Outside GST

There is a longstanding issue arising from the exclusion of petroleum products from GST. However, it is important to note that input tax credit on petrol and diesel has never been allowed, even under the earlier excise and VAT regime, and is unlikely to be permitted even if these products are brought under GST. Credit is generally available only on industrial-use fossil fuels such as furnace oil. The problem lies in the structural break in the tax credit chain for petroleum refineries: while capital goods and inputs used by refineries attract GST, the final petroleum products continue to be taxed under excise duty and State VAT. As a result, GST credits on capital goods cannot be utilised to discharge taxes on final outputs.

Unlike liquor, including petroleum under GST will not require another Constitutional Amendment, as GST on petroleum is already permitted under the Constitution (101st Amendment). The GST Council only needs to decide the date for its inclusion. A phased inclusion of petroleum products, starting with natural gas or Aviation Turbine Fuel (ATF), which are primarily used in industrial sectors, would be a good starting point.

The main argument presented by States for not including petroleum products under GST is the fear of revenue loss. Taxes on petroleum account for 11–17% of the own-tax revenue of the top five States in FY24, making them heavily dependent on this source.

GST Compensation Concerns

Another concern, particularly for southern states, is the discontinuation of the GST compensation cess and the demand for its renewal. When GST was introduced, states relinquished their independent taxation powers, and the authority to tax goods shifted from the state of origin to the state of destination. To offset this loss, the Centre had promised to ensure a 14% annual growth in states’ GST revenue for five years (2017–2022), calculated over the 2015–16 base year. This guarantee was supported through the imposition of a compensation cess at varied rates on luxury, sin, and demerit goods such as cigarettes, pan masala, gutkha, other tobacco products, soft drinks, and certain categories of automobiles.

Although the cess was originally expected to be phased out in 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected collections, compelling the Centre to borrow ₹2.69 lakh crore to fulfil its compensation commitments to the states. The government subsequently extended the levy and collection of the compensation cess until March 2026, solely for the repayment of these loans, while GST compensation to states was discontinued after June 2022. With the loans now nearly settled, the government anticipates a surplus of around ₹40,000 crore from the cess, which the states argue should be shared with them.

Many states, particularly those running large fiscal deficits and carrying significant debt, fear that reductions in GST rates or cuts in certain slabs will negatively impact their revenues. It is important to note that more than two-thirds of the states’ own tax revenues come from GST. Given this heavy dependence on GST as a stable revenue source, they are demanding a renewed compensation mechanism. Specifically, states are pressing for a minimum five-year compensation guarantee, using 2024–25 as the base year, along with protection of at least 14% annual revenue growth, mirroring the terms they enjoyed during the first five years of GST.

The government’s recent decision to levy excise duty by replacing the GST compensation cess on tobacco and related products will now form part of the divisible pool, of which 41% is shared with the states. It has also decided to levy a special cess on pan masala, which it plans to share with states through centrally sponsored schemes. Ensuring that states continue to benefit following the expiry of the GST compensation cess is a step in the right direction.

The states should be taken into confidence, and a consensus must be built between the Centre and the States.

The restructuring of the GST framework into a three-rate structure marks significant progress from the complex web of indirect taxes that existed before GST. The reduction of GST on essential goods and services is a step towards strengthening India’s consumption story at a time of global uncertainty. Yet, the journey of GST reform is far from complete, as several longstanding issues continue to impede the system’s efficiency. The next phase must focus on removing remaining distortions, strengthening compliance systems, enhancing trust between governments, and advancing towards a simpler, more transparent, and growth-oriented GST regime.

Author:

Mr. Ishant Deshmukh

Research Assistant – JP-SSSC